How to Grow Your Data Capital

The four stages of becoming truly data-driven | June 27th, 2017

The twin tides of digitization and artificial intelligence have risen so high that no business can ignore them. Information technology has come out from behind the curtain as the driver of value and innovation. Little wonder, then, that a recent issue of The Economist proclaimed that “the world’s most valuable resource is no longer oil, but data”.

As practically every human activity now generates a digital trace, the advantage lies with those who can exploit the insights that lie in the data. When will a customer buy? What’s the best product mix? When should we do maintenance? What makes my workforce the most effective?

Surprisingly, the algorithms that drive these insights aren’t the secret sauce. And although priced at a premium, neither are the data scientists who wield them.

The value lies in the data itself, in its potential when applied to your business.

Though there is much to be gained from using data to reduce costs, or optimize processes, that’s not the full story either. A well of data creates future possibilities and competitive advantage. For example, by delivering a connected car, Tesla gains unique and massive insight into driving patterns: a bulkhead against competitors, and a rich resource to leverage in future innovation.

The ability to generate this future potential through operating your current business is the ultimate definition of what it means to be data-driven: when value, and not solely decision-making, is being driven by data.

Growing data is a pressing business priority

The true value of data places it as a burning issue for every business. A plan to grow data reserves merits a prime place in every corporate strategy. But how exactly can you make that a reality?

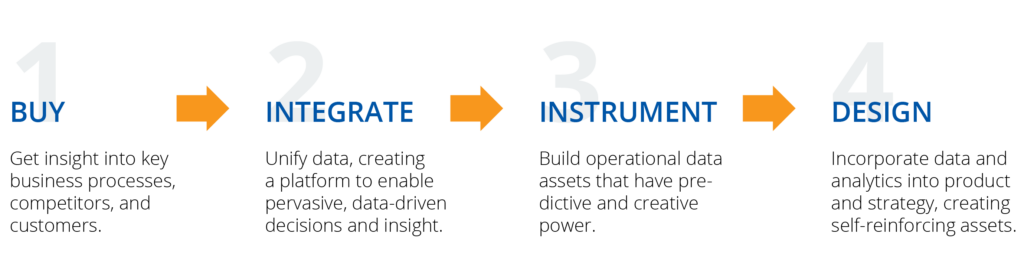

There are four levels of growing data investment: buy, integrate, instrument, and design. The truly data-driven engage across all of these.

Buy data

One of the quickest ways to gain insight is to buy data, and it’s nothing new to most businesses. Buying data has been industry practice for decades in the arena of consumer and competitive intelligence, thanks to information companies such as Acxiom, LexisNexis, or Hoovers. Financial data, weather and geographical data are all staple requirements for many businesses.

Through acquiring third party data, you can gain more insight into existing operations and improve decision support. However, available data for sale tends to be limited to large scale data sets, predominantly environmental in nature. Buying data enables the business, but you can’t buy your way to competitive differentiation.

Integrate your data

Even before the era of big data, companies generated a wealth of information that could be leveraged to fuel growth and create more value. The potential of integrating this information is high. Combining data sets tends to have a multiplicative effect on the data’s power, rather than merely additive.

Every system in a company is constantly creating data. However, data silos are a systemic problem that heavily constrain how useful this data is. Silos come from software applications and processes built in an era before the value of data was truly recognized, and one where resource constraints were more restrictive. The design of these systems is centered around the process they perform, in order to be most efficient. A natural side-effect of being process-oriented leads to semantic differences between business functions, and adds further complication: it is not unusual to encounter multiple different definitions of concepts such as “customer”.

Instrument for data

When you are really focused on using data to drive decisions and value, instrumentation is the next step to take. Instrumentation is the act of embedding data generation into processes and systems, reporting on their status over time. Thanks to the field of operations research, this concept is nothing new in business, but with increasing digitization, the scope for instrumentation is vast.

To give an example from software: the extent of software instrumentation used to be logging errors, in order to give support technicians hope of diagnosis. Now, it’s feasible to record every user interaction, every move of the mouse, and the questions we can ask extend further: not only “why did something go wrong”, but also “how easy is this product to use?” Or another example from retail, where radio beacons now allow the monitoring of foot-traffic through a store, enabling assessment of the effectiveness of a physical layout.

The combination of instrumentation and data science allows us to gather detail and solve problems which would previously require prohibitively expensive human intervention.

Design for data

Any organization deeply invested in the above three levels is already in a strong leading position, but there is one step further in realizing the potential of data. If you truly comprehend your data’s power, then design activities around its accumulation and exploitation, building data as a strategic asset.

To reach this point is to begin to have an answer to the tech giants of Google, Amazon and Facebook. As data-native companies, their agility, accumulation of data, and financial power allows them to challenge convincingly in new markets.

The essence of a business designed for data is that the delivery of the product or service generates data that further enhances the service, and creates a platform for the next steps of innovation and expansion. Customers aren’t viewed as isolated recipients, but as part of an ecosystem in which their participation makes the product better for everyone. Feeding off this customer-generated data, analytics and artificial intelligence are used as part of the product, in comparison to the out-of-band applications of the previous three stages.

Data is a defensible advantage

The effects of building a company with data can be remarkable. Today’s advances in artificial intelligence bring major efficiencies and new capabilities, but have one driving trait—an insatiable thirst for data. Data is not a fungible commodity, and so its accumulation provides a daunting hurdle for competitors. This is such a compelling advantage that perhaps, as the Economist observes, we may even need a new kind of anti-trust approach in the future.