Can You Hear Me Now? How to Communicate with Remoties: Part 3

February 4th, 2016

In Parts 1 and 2 of this series on effective communication with remote colleagues, I looked at our preferred scenarios and best practices for instant messaging and video conferencing. This week, I’m sharing some thoughts about yet another important medium.

Phone Meetings

At Silicon Valley Data Science, the apps we use for phone meetings are very similar to the apps we use for video conferencing: many of them allow for dial-in audio in addition to VOIP or video access. (And, of course, there are actual phones.) In fact, I debated whether to separate the two categories or combine them for the purposes of this series, but decided in the end that phone meetings do indeed have distinct use cases.

Many of the same best practices that apply to video conferencing also apply to phone meetings, and vice versa. Please refer heavily back to the most recent post. In all honesty, the best practices in this post are more about good calendaring than they are about using the phone. Still, I trust you’ll find them helpful.

When to use them

When the flow chart is complicated. Perhaps you have a simple question for a colleague, but it comes with a set of follow-up questions that will vary depending on the answer to your original question: this is the perfect scenario for a quick phone call. This kind of call is typically impromptu and unscheduled.

When bandwidth is an issue. Video is ideal because of the additional visual cues it provides, but sometimes you just don’t have the internet bandwidth to support it. Especially when someone is in transit or making the best of shaky hotel wifi, sometimes the phone is the best way to go. Note that it’s completely fair to use a mashup of phone and video: sometimes, we’ll use the phone as the most reliable audio source, especially when internet bandwidth may drop out unexpectedly, but also use muted video as an auxiliary medium for the benefits it provides.

When it’s off the record. One of the major advantages of IM and email is that those formats leave a written record that you can refer back to. But sometimes you may want to avoid leaving documentation of a particular conversation. This can happen for nefarious purposes, sure, but there are also times when you may wish to discuss a delicate issue off the record for legitimate reasons. When that’s the case, the phone can provide an atmosphere that’s just the right balance between personal and private. Think of Catholic confessional booths, in which the priest is separated from the parishioner by a screen: sometimes it’s easier to talk frankly when you don’t have to maintain eye contact or a poker face. These occasions are hopefully few and far between in your organization, but they will come up.

A few best practices

Knock first. This bit of advice may be controversial, but: don’t call your colleagues in the middle of the workday without any warning. You don’t have to schedule every call in advance, but at least use IM or a text message to ping your teammate first and inquire as to whether they are free to talk. The ideal version of this is similar to the “note through the mailslot” approach that I described in the first part of this series: let them know what you need to chat about and roughly how long you expect the conversation to take. That way, they can manage their own time effectively and either make space for the call right away or make a counter-offer to defer it a bit. The counter-offer might consist of talking then but selecting another medium such as IM, for instance, if the topic can’t wait but they are in a place where they can’t easily speak openly or take a call. This exchange of information might seem like extra work, but it’s a lot friendlier and more productive than setting someone’s ringer off and then making them listen to a voicemail.

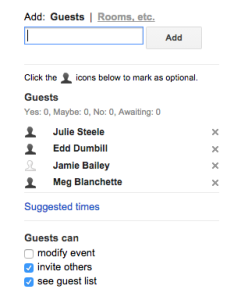

This Google Calendar screenshot shows my teammate Jamie as an optional attendee.

Distinguish between required and optional attendees. For group meetings, especially regular standing meetings whose exact purpose and agenda may shift from instance to instance, it is often the case that certain people must absolutely be present while others would like to stay in the loop but aren’t critical to the process. It’s very useful to distinguish between these categories in the meeting invite itself, for two reasons. First, it helps invitees to properly prioritize conflicting time commitments or decide for themselves whether there’s a better use of their time that day. Second, it prevents you from wasting time at the beginning of meetings by waiting for attendees who may or may not actually show up (or matter much to the productivity of the meeting).

Include an agenda in the meeting invitation. This practice serves two important functions. First, it saves precious minutes during the meeting itself by providing context ahead of time, and giving participants adequate notice of any metrics required or other research that might be necessary so they can come prepared. Second, it gives everyone on the call a program to stick to. If the discussion strays too far into the wilderness, anyone can easily rope it back in by referring to the agenda to get back on track.

Note: Make sure the agenda includes any decisions that need to be made. This is critical to the success of the required/optional attendee tactic. You may not think a given colleague needs to be part of a particular decision, but they may feel strongly about having input. Including the decision on the meeting agenda in the invite helps them decide whether or not they need to attend. When you start making decisions that aren’t on the agenda, you create a kind of paranoia that makes people feel the need to accept every invitation that comes their way just in case, negating the utility of the required/optional attendee bucketing described above.

Be considerate in your scheduling. While no one enjoys too many back-to-back meetings in a row, what we’ve come to call “calendar swiss cheese” is even worse. Especially if you work as a developer or in some other creative role, it’s critical to have large blocks of time in which to get focused and enter a flow state. Context switching is expensive: interrupting your morning with a half-hour meeting costs not just that half hour, but also 15 minutes on either side of that chunk of time to switch gears. Minimize this overhead cost by clustering meetings together. (You can also do yourself a favor by engaging in “defensive scheduling” and blocking out chunks of focus time for certain projects, especially when you get close to deadlines.)

Another friendly calendaring technique: schedule meetings to end five or ten minutes before the hour or half-hour — and then stick to it. Especially if you’re going to stack meetings up next to each other in a block (which you should), building in “bio breaks” for snacking and restroom trips (or, in technical terms, input/output) is essential. This buffer also helps prevent the domino effect. When one meeting runs long early in a block of them, this buffer time will prevent you from being late for every subsequent appointment. Pro tip: you can change the default meeting lengths in Google Calendars to accommodate this by checking the “Speedy meetings” box under General Settings.

Conclusion

While phone meetings lack the body language and facial expression cues that video provides, this can afford a level of discretion that sometimes comes in handy. The phone also offers more flexibility over video because of its lesser bandwidth requirements. Just make sure that this flexibility doesn’t become an excuse for disorganized or oversubscribed meetings.

Next week, in the final installment, I’ll take a look at how we use email. In the meantime, leave me a comment and tell me how you use phone meetings and what your best practices are.